The

Revd Edward Wilson

Curate 1806-1854

The Revd Edward Wilson was Curate

of St John’s for 48 years. He was appointed in 1806 at the age of 24,

having been born in 1782. There is a gap in the parish registers which

lasts until 1813, and we do not find any entries with his signature

until then. This may be

because, in common with many other clergy of the day, if they had the

means, they frequently employed less well-off curates to officiate for

them. This was evident throughout Edward Wilson’s cure, for there

are plenty of examples of other men taking the services at the chapel,

but it may also have been the case that he suffered from periodic bouts

of ill health or depression, as we shall see.

Edward

Wilson was the son of another Edward Wilson, who was also a clergyman

and who served as Incumbent of Chapel Allerton, near Leeds in the

County of York for 35 years. He was born in Kescadale, Newlands, near

Keswick on May 6th, 1761, and died at Keswick on July 2nd,

1835

His

son, Edward Wilson was a family man. His wife was Anne Wilson, and

during his time as curate, they had no less than seven children born

and baptised at the chapel. There was at this time no parsonage in the

parish, so the family lived at a variety of addresses.

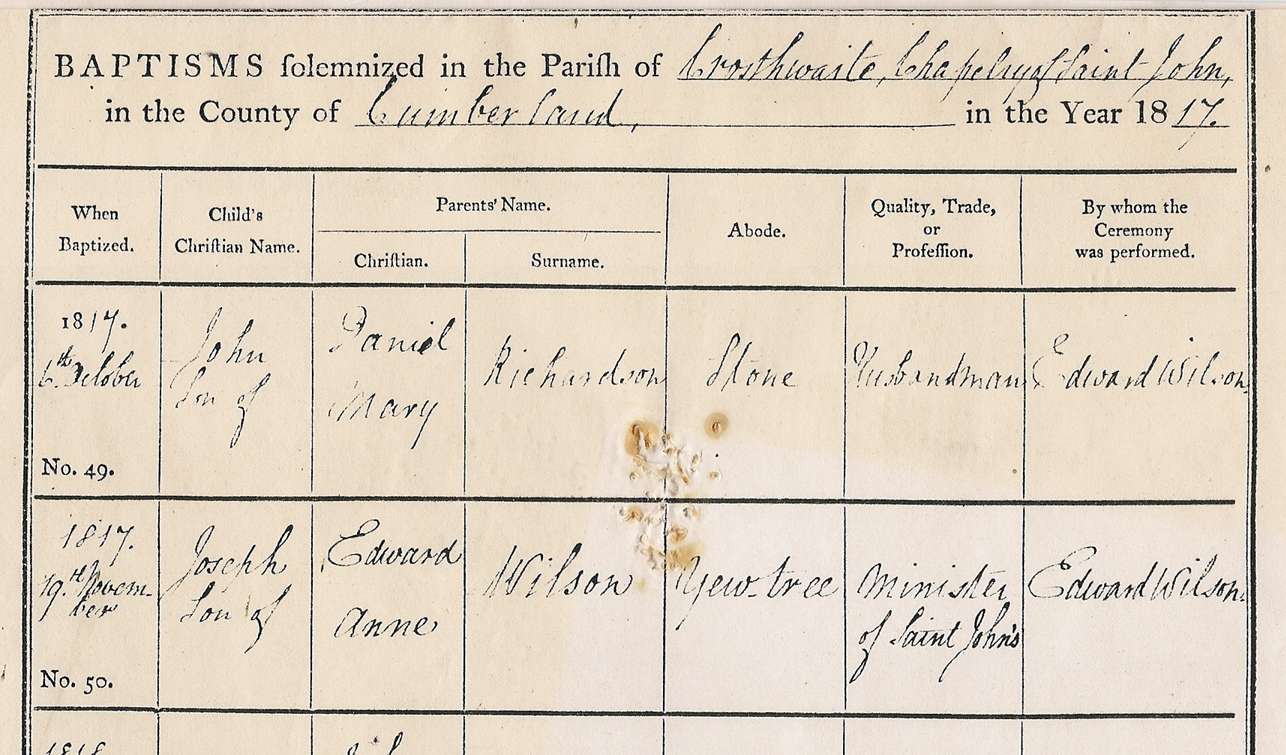

Their first child, Joseph, was baptised on November 19th, 1817

by Edward himself. Interestingly, the immediately previous

entry (6th Oct 1817) is for the baptism of John Richardson, son of

Daniel and Mary Richardson of Stone. John Richardson became a

noted writer of dialect poetry and prose and wrote later of ‘Priest

Wilson’.

His

son, Edward Wilson was a family man. His wife was Anne Wilson, and

during his time as curate, they had no less than seven children born

and baptised at the chapel. There was at this time no parsonage in the

parish, so the family lived at a variety of addresses.

Their first child, Joseph, was baptised on November 19th, 1817

by Edward himself. Interestingly, the immediately previous

entry (6th Oct 1817) is for the baptism of John Richardson, son of

Daniel and Mary Richardson of Stone. John Richardson became a

noted writer of dialect poetry and prose and wrote later of ‘Priest

Wilson’.

The Wilson’s address is given as Yew Tree, though, whether this

was the farm or the cottages is not apparent, and before they

moved house, Anne had given birth to two more sons, Alfred, who was

baptised on September 2nd 1819, and Edward, baptised on

August 4th, 1821.

During the next few years, Edward Wilson baptised and buried regularly

those parishioners who needed his ministrations, but in December 1824,

other clergy sign the register for a year or two, with only the

occasional signature of Edward Wilson. Perhaps he suffered a

period of illness. Even when his fourth child, a daughter this time

named Mary Anne, was baptised in 1825, someone else took the service.

By this time the family had moved from Yew Tree to Piet Nest (Low Nest

today). Again, in 1827 when Daniel, his fourth son was born, he did not

baptise the child himself. Parson and White’s Directory of 1829 records

that The Rev. Edward Wilson, Perpetual Curate of St John’s

was resident at Piet Nest.

Apart from the occasional signature, it was not until May 1829 that he

started to take services regularly again. In 1831 he baptised his sixth

child Thomas, but the following year sorrow came to the family with the

death of Edward, his third son, at the age of ten. The curate

took his son’s funeral himself. At some point during the next two years

the family moved back to the other side of High Rigg, leaving Piet Nest

for Bridge House, and here, in May 1834, to their joy (one imagines) a

second daughter was born and baptised. This was the last

child Edward and Anne were to have.

Edward Wilson continued to serve the parish for another 19 years.During

this time, the ‘parsonage house’ (presumably Bridge House) became unfit

for residence, for we have among the parish papers a licence from the

Bishop of Carlisle permitting the curate to be absent from the benefice

from January 1842 until December 31st, 1843, ‘due to the

dilapidated condition of the house’.

This was not the only dilapidated building either, for in 1845-6, the

church itself was rebuilt, because it too needed repair.Whether Edward

Wilson ever moved back to Bridge House is not clear.

Certainly, towards the end of his life he lived in Keswick,

where he died.

He was greatly respected by his parishioners as this little token

illustrates:

On Tuesday, November 10th 1846, a Yew Tree presented by Sarah

Stanley of Row End was transplanted in the churchyard ‘as an ornament

to the Chapelyard as a token of veneration and esteem for her beloved

pastor, the Reverend Edward Wilson, Keswick.’ The tree was planted by

the Schoolmaster, John William Crowe and ten of his pupils, John

Edmondson, John and Robert Cartmell aged 13 and 14 of Piet Nest (Low

Nest), William Cartmell (13) of Smaithwaite, Joseph Allison

(11) of Goosewell, William Edmondson (9), John Williamson (9) of

Lowthwaite and Christopher his brother (11), Thomas Allison (9) of

Goosewell and John Cartmell (9) of Bridge End.

Perhaps this is the Yew tree now in the corner of the churchyard near

the Diocesan Youth Centre, or possibly, the Irish Yew near to the

church?

In 1852, Sarah Margaret died in Keswick and was brought to be buried at

the chapel by her now aged father. She was 18 years old. Edward Wilson

was to follow her only two years later, when he was buried in St

John’s-in-the-Vale churchyard at the age of 72. His grave can easily be

found near the West end of the church under the rhododendrons. The

stone commemorates his father as well. Anne Wilson joined her husband

eleven years later when she died, also at the age of 78.

We come now to the sad and tragic death of Edward. This report appeared

in the Kendal Mercury on Saturday 15th July 1854 and speaks

for itself.

'On the morning of Saturday last, the town of Keswick was thrown into a

state of excitement, by the painful report that the Rev. Edward Wilson,

Incumbent of St John’s-in-the-Vale, had committed suicide in

an outhouse adjoining his dwelling, by cutting his throat with a razor,

about six o’clock that morning. The deceased had been incumbent of St

John’s–in-the-Vale for a long period of 48 years; and was held in great

esteem and respect. The inquest on view of the body was held on Monday

last, before W. Lumb, Esq., coroner for the Western Division of the

County of Cumberland, and a respectable jury, at the Royal Oak Hotel,

Keswick.

Thomas Wilson, who was extremely affected, on being sworn, said,

" I am a son of the deceased, who would be 73 years of age

next Christmas. I last saw him alive on Friday night about eleven

o’clock.On Saturday morning about six o’clock, my mother came into my

room and said she had lost my father. I got up and went into two or

three rooms, and then went into the garden to see if the door was

bolted; it was fast, and I then knew he must be on the premises. It

was

quite an unusual thing for him to go out in the morning. I then

went accompanied by the servant, into a place – a barn

formerly – at present used for lumber. I had to go through the yard to

get to it. I could not see him. I told the girl to open broad the doors

to throw in more light. I then saw him lying on his left side dead,

from a wound on

his throat. His body was quite warm. I had no suspicion that any one

else had done it; there is no doubt that he had done it himself. When I

returned from College about ten days ago, I found a marked difference

with him; before that he had not been at all well; he had suffered from

influenza; complained of intense pain in the head, and his feet were

quite cold. He had been in a low desponding state, and took no interest

in anything since my brother’s death about two months ago; he was of a

very nervous temperament; he had done no regular duty for 30 years. I

made no remark to the family about the marked difference in

him that I noticed".

The Rev. R Mulcaster, on being sworn,

stated that he was curate of St John’s in the Vale, and had known Mr

Wilson’s family for about three years. He had been about 18 weeks in

his curacy, and lived in Keswick. He had observed great alteration in

the deceased since his son’s death, and recommended Mrs Wilson to go

with him to the sea side. He never observed any derangement;

he was not cross; he desired to be alone; never gloomy and

sad; lived quietly, and was very abstemious. I saw him on Monday last;

he would not join in conversation; he was quite capable of transacting

parochial

business; he kept pressing his head with his hands; he said” what nice

cold hands you have got; my head is very hot”.

The jury

returned a verdict “that the deceased destroyed himself

during temporary derangement.”’

This report reveals much more about

Edward Wilson. It may be that he did in fact suffer from periods of

depression, and his regular use of curates to look after parish

affairs, while common among clergy of the time, may also have been due

to his poor health. Clearly the death of his son only two

months earlier, and of his daughter two years earlier, had affected him

deeply. This was the third of his children to predecease him.

He is said to be nervous, desiring a quiet life, and very abstemious.

Nevertheless, the mention that he was held in great esteem and

respect is supported by the planting of the tree in the

churchyard already referred to.

The family must have been reasonably well off. As an incumbent

of St John’s, his stipend at the time he took up his

incumbency was provided from an ancient endowment. On 15th June, 1719,

‘certain of the inhabitants (of the parish) had contributed to the

procuring of Queen Anne’s Bounty for the augmentation of the curacy’

and a declaration of the “intention” of such of the inhabitants as had

so contributed’ had been made. (Report of The Charity Commissioners

dated during Edward Wilson’s incumbency). This stated among other

things that the curate should teach the children of the Chapelry, and

that ‘as the inhabitants of the chapelry had contributed to the

obtaining of the royal bounty, and beside that, paid the ancient yearly

allowance and stipend, the school should be free for the benefit of the

whole chapelry; and if the “curate should refuse or be disabled as to

teaching school himself, he should allow another fit person £5 per

annum for that end and purpose” This was signed by 37 inhabitants, by

two curates previous to 1773, and by John Wilson in 1773 (also a

curate), stating that he promised to perform all the particulars

required except the clause in which the school is mentioned as being

free, but he agreed to teach the same during his pleasure at a

reasonable quarter

pence, or to allow £5 per annum. It was signed by another curate in

1786.

This ancient stipend was £3-7s-11d, being a fixed rate collected from

every householder and paid to the curate. The statement then goes on to

say that ‘the Rev. Edward Wilson teaches school, receiving quarter

pence from the children according to what they learn ---- and that

Mr Wilson has no intention to discontinue teaching school,

and if he should, he has no objection to pay £5 to another

schoolmaster.’

In addition, Mr Wilson also receives ‘27s being the interest of a

turnpike ticket for £30 purchased with £27 of ancient chapel

stock but it is not known how this fund arose.’

A Terrier of 1777 lists the various properties purchased with the

sum of £200 given by the late John Gaskarth, the £200 from

Queen Anne’s Bounty, and £100 contributed by the inhabitants of the

chapelry. These lands (Sykes, Birkhow Sykes and Dale-Bottom) were said

to be worth about £30-10s yearly. There were also funeral,

baptism, and churching fees. Altogether this seems to add up to about

£35 per annum.

Whether this would have been sufficient income to support a curate we

cannot say, but it seems doubtful that the curate could have

afforded to pay other clergy and a schoolmaster too without

private means. In the case of Edward Wilson, we know

perfectly well that he did for long periods employ others,

including, presumably, the schoolmaster Mr Crowe mentioned

before.

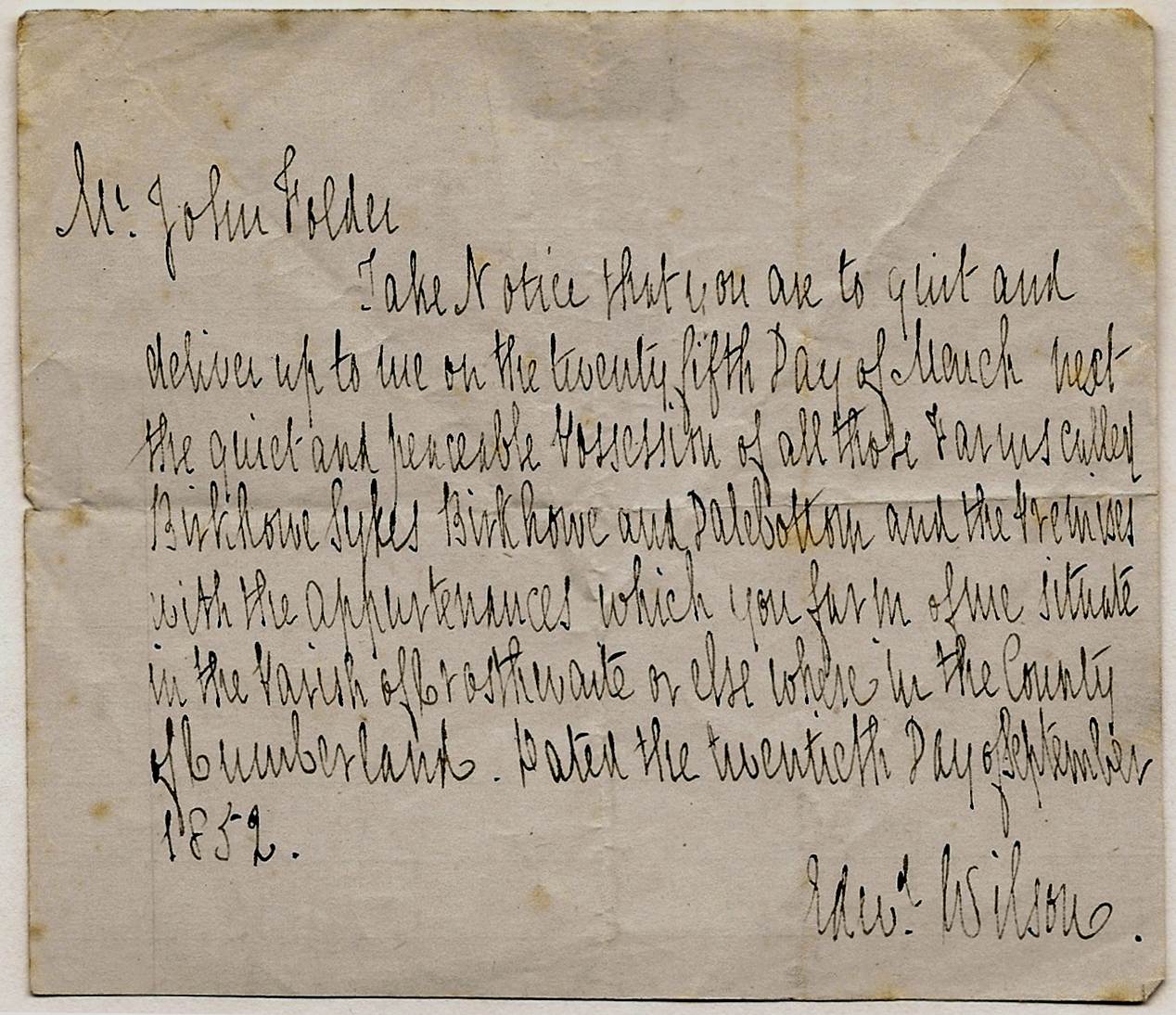

An interesting letter exists among the church papers. It is

from Edward Wilson to John Faulder, his tenant at Sykes, and

reads:

“Take notice that you are to quit and deliver up to me on the

twenty-fifth day of March next the quiet and peaceable possession of

all those

farms called Birkhowe Sykes, Birkhowe and Dalebottom and the premises

with the appurtenances which you farm of me situate in the

Parish of Crosthwaite or elsewhere in the County of Cumberland. Dated

the twentieth Day of September 1852.”

“Take notice that you are to quit and deliver up to me on the

twenty-fifth day of March next the quiet and peaceable possession of

all those

farms called Birkhowe Sykes, Birkhowe and Dalebottom and the premises

with the appurtenances which you farm of me situate in the

Parish of Crosthwaite or elsewhere in the County of Cumberland. Dated

the twentieth Day of September 1852.”

Among those who were taught by Edward Wilson was John Richardson, the

local dialect poet, builder of the church, the school and the vicarage,

and eventual schoolmaster.

Of priest Wilson he says in his humorous tale in dialect, “T’ Barrin’

Oot”,

“I went to

St Jwohn’s Scheull, when Preest Wilson was

t’maister. He

was rackon’t a varra

good maister. Sartenly, he was parlish sharp on

us at times; an’ some

o’t’ laal uns war nar aboot freetent to deith on’im.”

Among the subjects that Priest Wilson would have taught John

Richardson were Latin and Greek, and reading, writing, and

arithmetic, as required by the declaration of 1719 already referred to.

It appears that Edward Wilson did fulfil his obligation to teach in

the school himself for some years at least.

The wording on the gravestone tells us little more, merely saying

that he was ‘Laid to rest, July 11th 1854, aged 72 Years,

Incumbent of this parish for 48 Years’